May 6, 2020

Progress, But Hardly Perfection: The Reality for India's LGBTQ Community

Merryn Johns READ TIME: 13 MIN.

Just a few years ago, student Debottam Saha used Grindr to meet a man in a Delhi park. "I'd chatted with the guy on text, but most of the time, you end up with strangers," he said. Such hookups came with risk. Saha's date threatened to out him, then pulled a knife. Saha paid him three thousand rupees (about $40) and fled.

Such extortions were common occurrence under Section 377 of the Indian penal Code, which outlawed sexual activities "against the order of nature"– including homosexuality.

On February 6, 2016, the Court reviewed the batch of written petitions that claimed a violation of constitutional rights under Section 377 and filed to challenge its constitutional validity on the specific ground that it criminalizes consensual sexual intercourse between adult persons belonging to the same sex in private.

This round of petitioners included the Naz Foundation (India's leading health and HIV/AIDS NGO), and Saha, the young student who had been blackmailed at knifepoint by his Grindr date. Navtej Singh Johar, an award-winning Bharatanatyam dancer, also filed a petition in the Supreme Court. Joining him were celebrity chef Ritu Dalmia and high-profile hoteliers Aman Nath and Keshav Suri.

It would be another two years before the Supreme Court and chief justice Dipak Misra began hearing the petitions. Defense of the law focused on anal sex as "unnatural" with supporters claiming it helped to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and therefore, should be retained. But in a 50-page judgment and a unanimous verdict, the Court abolished Section 377. In the judgment, Justice Malhotra wrote: "Homosexuality is a natural variant of human sexuality," and acknowledged that Section 377 "creates an artificial dichotomy" that violates the constitutional right to dignity and equality for the LGBTQ minority.

On September 6, 2018, the repeal of Section 377 ushered in a new era for India's LGBTQ community – or was supposed to.

"Section 377 has not been repealed," claims Jo, who offered their first name only, the digital editor and creator of Gaysi Family, a blog and safe space for gay de-sis (LGBTQ people from the South Asian Subcontinent). "It has just been amended to not put gay sex in the same list of criminal offenses as bestiality and pedophilia."

Even so, the amendment of Section 377 sent ripples around the world. When the Zimbabwean Court handed down its verdict in favor of Rikki Nathanson, a transwoman who had been abused by police, it was in part because High Courts "listen to each other," and their rulings, says Jessica Stern, director of OutRight Action International. Additionally, activists in Singapore are now pushing for the repeal of its own colonial anti-homosexual law, coincidentally also titled Section 377.

The Struggle Against Section 377

"Harassment and blackmail were common," says Bansri Manek, a young queer woman who found life under Section 377 so oppressive toward the LGBTQ community that she emigrated to the United States. Manek says she knew cases where gay men were raped by police officers while in custody or men who had to pay to be released because offenses under Section 377 were non-bailable.

The movement to amend Section 377 began in 1991, and by July 2009, certain aspects of the law were struck down as unconstitutional by the Delhi High Court. Many activists believed Section 377 would be completely overturned by the Supreme Court of India. But on December 11, 2013, the Court declined to amend the law.

"We were all euphoric, ready to party, thinking we're going to get this act repealed and I remember being at the airport wanting to take the flight to Delhi to celebrate and the verdict was against the Delhi High Court, and I remember crying at the airport," recalls Onir, India's leading gay filmmaker, and a high profile spokesperson for LGBTQ rights.

"The false hope that it would be repealed left long-lasting scars and perhaps enough fury to make it work next time," says Manek. "The Indian economy was progressing rapidly, and more people started to move to larger cities for work, away from home. They were freer to explore their queer side, and this developed a crop of activists who did not want to go back into the closet when visiting their parents in the small towns."

In 2015, 1,491 people were arrested under Section 377, including 207 minors and 16 women, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

For India's homosexuals, such persecution was the norm unless they were shamed into celibacy, secrecy, or hid in arranged marriages. It took a collective of outspoken artists, activists, and entrepreneurs to finally get LGBTQ rights on the agenda in India.

Onir recalls Mumbai in the 1990s when gay parties and nightclubs were underground and subject to police raids.

"I always left before the police came, but it's not nice to know that your friends are being humiliated and that you could have been one of them," he recalls.

Onir's films also suffered. "My Brother Nikhil" (2007) and "I Am" (2011) are often listed in the top 100 Indian movies of all time but struggled to find distribution. "My Brother Nikhil," about an Indian swimming champion who discovers he has HIV/AIDS, was considered untouchable by distributors.

Progress, But Not Perfection

While the Supreme Court justices acknowledged that the "social ostracism against LGBT persons prevents them from partaking in all activities as full citizens, and in turn impedes them from realizing their fullest potential as human beings," Jo from Gaysi says that "an amendment in the Supreme Court cannot guarantee the social acceptance of the community since homophobia is so deeply ingrained in our system. We, as a country, need to decolonize the way we see sexuality because it was the Victorian rule from England that brought in the idea of homosexuality being 'unnatural.'"

But Jo, who identifies as a lesbian, acknowledges that the amendment had an immediate positive effect. "For a whole week, every newspaper in the country was talking about queer lives and narratives, and that reached almost all corners of the country, making way for more engagement in the grassroots organization."

The language in the ruling was strong: "History owes an apology to the members of this community and their families, for the delay in providing redressal for the ignominy and ostracism that they have suffered through the centuries," wrote Justice Malhotra.

But colonial history must be unlearned for the law to have a social impact. Most LGBTQ Indians assert that Section 377 was not a product of Hindu culture, but a law imposed by an alien empire to help stifle the polymorphous sexuality of an ancient culture. And yet it has led to a mindset that India, the world's largest democracy, still struggles to shake.

REPRESENTATION MATTERS

One way is through artistic expression, a mode that is embraced by Hindu culture. LGBTQ cultural exchange organization InsideOut works with the Naz Foundation to support LGBTQ-identified artists with an art prize.

"We want to use the arts and culture route to enable a better understanding of what it means to be LGBTQ+ in India," says Shivraj Parshad, organizing committee member of the InsideOut Art Prize. "An inclusive society means accepting people for who they are and embracing difference as a good thing that strengthens society. LGBTQ artists need to have a space where they can safely produce work that is about their own lives and use that art to help society better understand them. Seeing yourself represented in your culture and controlling the way that you are represented are important things for any group."

Speaking on behalf of the artists supported by InsideOut, Parshad said the mood is positive. Post-377 India has removed the fear of legal prosecution, "but social change – so that we can all feel safe and equal – takes longer," Parshad explains. "We think that art is an important part of that change. Entries in this competition have been an expression of that struggle, experience, interpretation and as this year's theme suggests, 'Awakening.'"

Fashion has also become a powerful way to sell LGBTQ freedoms to broader society. New Delhi fashion accessories brand Fastrack made a short film interviewing gay couples and used the hashtag #AddColoursToLove to promote it. Levi's launched #ProudToBeMore, a campaign that featured a handful of high-profile LGBTQ artists and models. With rock-video style imagery and voice-over narration, the campaign featured four out and proud creators: Onir, Sushant Digvikar, Priyanka Paul and Aravani Art Project.

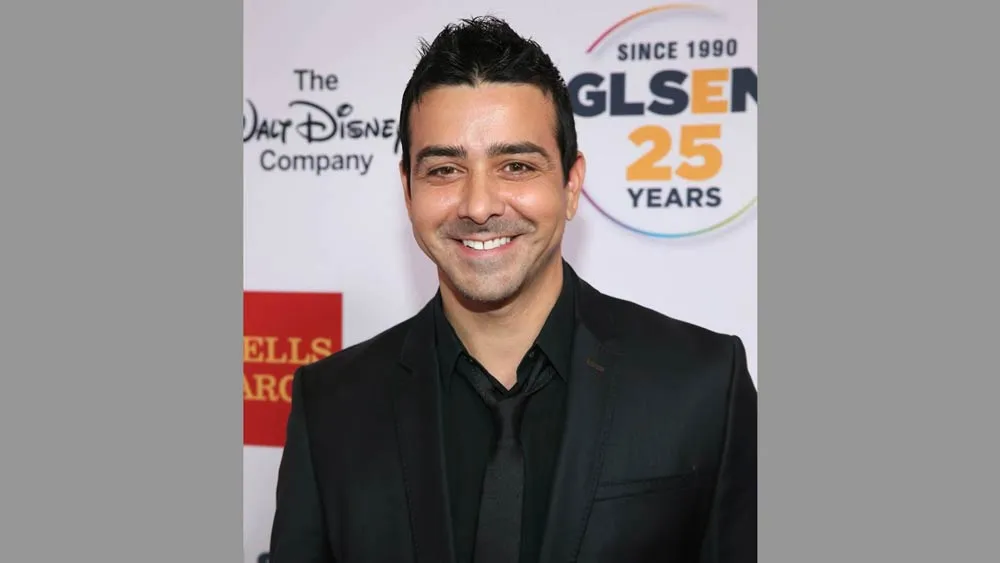

Singer, performer and drag star Sushant Divgikr, also a former Mr. Gay World, says there is "a long way to go" before LGBTQ people are accepted in India, and so he supports the Closeup India #FreeToLove campaign.

But while he rejoiced when Section 377 was amended, Divgikr says his career as a queer performer had flourished under the Indian Penal Code because audiences understood the law as archaic, "one of the many ridiculous ideologies left behind by the British during their oppressive reign over our country, so that they could run their propaganda, and divide and rule people based on religion, caste, sex and orientation."

Nevertheless, he says, the amendment has "definitely opened doors to many people coming out of the closet and expressing themselves freely. I've been fortunate to have been alive to witness this landmark decision and to tell people how much has changed in terms of public perception and how people look at the community."

Changes include "entire series where the protagonist is gay, and the character is very normalized and fits seamlessly with the other characters." Since the repeal, Divgikr appeared on MTV India as drag queen RANI to judge the beauty makeover reality TV show "Lakme India." He has performed all over India with international drag artists Lady Bunny and Peppermint and was also the youngest LGBTQ individual to be on the 50 most influential Indians list announced by GQ magazine.

But while arts and culture have embraced LGBTQ rights, the broader population – especially in rural areas – will take more time to come around. Even in corporate India, the feeling is hesitant, with 57 percent of people saying their company would never hire LGBTQ workers, according to Shivangi C., a journalist at The Times Of India.

WOMEN AND THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY

Lesbians are often left out of the conversation since Section 377 was modeled on a 16th-century anti-buggery law. And lesbians often choose to keep a low profile due to the epidemic of violence against single or visible women in India, including girls.

"I think violence against women comes from a long tradition of patriarchy, but it's also economic," says Onir. "Very often, men feel that their space is getting taken over by women. More and more women getting into the workforce and being seen as powerful is threatening to the patriarchy."

"Intersex folks (Hijrah) are recognized as the third gender in India but are not accepted in mainstream society at all and are usually dependent on begging to survive," says Bansri Manek, who believes that the prejudice against women and transgender people is rooted in ideas of purity. "Mugal and British invaders raped local women as a means of creating fear and oppression. The invaders left, but this mentality never changed. Indian parents kept women locked away, dependent on someone for survival – parents, then husband, and then their kids."

"Trans and Hijrah people are almost not considered human, making them an easy target. The police do not take their reports seriously, and in a lot of cases, it is the police who harass them," says Manek.

Onir says that the third gender has always played a key role in Hindu culture, noting that in the epic "Mahabharata," the war between the Kauravas and the Pandavas ends "because of a transgender warrior. Until the British brought in Section 377, there was nothing that criminalized homosexuality. I'm not saying homosexuality was celebrated, but at the same time, it was not stigmatized. Hindu culture had much more matriarchal society."

Things are changing, says Onir. "Yesterday, a friend of mine who is a fashion designer had gone to a party with his friends at a nightclub in Delhi and he was dressed in a hat and a sari. People started heckling and abusing him, and he got injured. But he stood up for his rights and the management threw the other guys out."

THE ROLE OF MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY

After Section 377's amendment, large companies like Airbnb and Durex India ran campaigns or added a Pride rainbow to their logos to show solidarity.

"We as marketers and advertisers have the tool of projecting to media and, therefore, to the nation. I feel we should use this powerful weapon to bring some progressive change," says Priti Nair, director of ad agency Curry Nation.

Grindr has also taken on an activist role since the amendment of Section 377. According to Jack Harrison-Quintana, director of Grindr for Equality (G4E), the company uses technology to help the LGBTQ community in India and other countries where being queer is dangerous or illegal.

This assistance includes the country's first LGBTQ service finder tool where Grindr users can access LGBTQ rights groups, sexual health services such as HIV testing, mental health services, and legal aid in their local area. And the app works with many of the country's 22 official languages.

"Despite the tremendous milestone when Section 377 was amended, people around India can still face discrimination in all areas, so much more education and visibility raising must be done before mindsets can be challenged," says Harrison-Quintana. "We are working toward a world that is safe, just, and inclusive for people of all sexual orientations and gender identities."

So, can LGBTQ Indians now openly seek love, sex, and romance?

"Stigma is still there, shame is still there, fear is still there, but at least we cannot be harassed legally, and that is a big win. If I take my girlfriend to visit India, I don't have to be worried about getting into serious soup for holding hands with her," says Manek.

And for gay men who want to visit India and meet other gay men, Rohit (not his real name), who works in inbound travel and tourism, offers encouragement. "India is a very special destination; I would say it's the heart of Asia! The general sense of welcome goes up a notch when the traveler knows that they won't be discriminated against," says Rohit. "Also, I don't think that a traveler would ever be subjected to anything close to the discrimination locals faced be-fore the turn-around happened."

"A couple of years ago, when I was in Berlin for Pride, I thought, shit, will I get to see in my lifetime people who love each other allowed to walk hand in hand without fear from the law?" says Onir. "Society will take a while, but when you're empowered by law you can fight society." Now, if the Censor Board asks him to delete something from one of his films he can refuse. "In 2017, with the film 'Shab' I was told, 'Can't you make the gay couple look like brothers?' No one can tell me to do that anymore."

"It is kind of ironic," says Onir, "because sex is just one aspect of being gay. For us, now the real journey is towards civil rights." This includes the right to marry, adopt children, or serve in the military.

But will the amendment of Section 377 usher in a new era of homonormativity? Indian police banned Mumbai Pride on February 1, 2020, to prevent the parade from turning into an anti-government protest of the Citizenship Amendment Act, which gives immunity to various religious groups–other than Muslims. And while on November 26, 2019, a bill was passed prohibiting discrimination against transgender people in education, employment and habitation, they must first register with the government and submit proof of gender confirmation surgery, which activists say violates the bodily autonomy of trans people.

With the rise of right-wing Hindu nationalism in India, the gains that were made by casting off colonial-era laws such as the anti-sodomy Section 377 may face new challenges posed by an emboldened faith-based majority government.

Merryn Johns is a writer and editor based in New York City. She is also a public speaker on ethical travel and a consultant on marketing to the LGBT community.

This story is part of our special report: "EDGE-i". Want to read more? Here's the full list.